Tutorial on solving Markov Decision Process with linear programming

Published:

In this post, we discuss the hands-on implementation of the Markov decision process (MDP) as a tool to solve the decision-making process of a dynamic system by leveraging the linear programming method. First, we will briefly discuss the definition of MDP. Then, we will consider a use case of MDP to determine the optimal policy for industrial machine maintenance. Based on this use case, we will discuss how to formulate a suitable MDP representation. Finally, we will solve the MDP representation through linear programming techniques to obtain the optimal policy for the decision-making process.

Versi Bahasa Indonesia tersedia di sini.

Quick Introduction

A Markov decision process (MDP) is a mathematical model that is often used for the stochastic decision-making process of a dynamic system. In this context, the system’s outcomes are influenced by both random factors and the decisions made by an agent, who must make a series of sequential decisions over time. The basic building block of an MDP consists of 4 tuples $(S, A, P_a, R_a)$, where:

- $S$ is a set of states, which is often called state space.

- $A$ is a set of actions called action space ($A_s$ would be the set of available actions from state $s$).

- $P_a(s,s’) = P_a(s_{t+1} = s’|s_t=s, a_t=a)$ is the probability of the action $a$ in state $s$ and time $t$ will lead to state $s’$.

- $R_a(s,s’)$ is the immediate (or expected immediate) reward of taking action $a$ to transition from state $s$ to state $s’$.

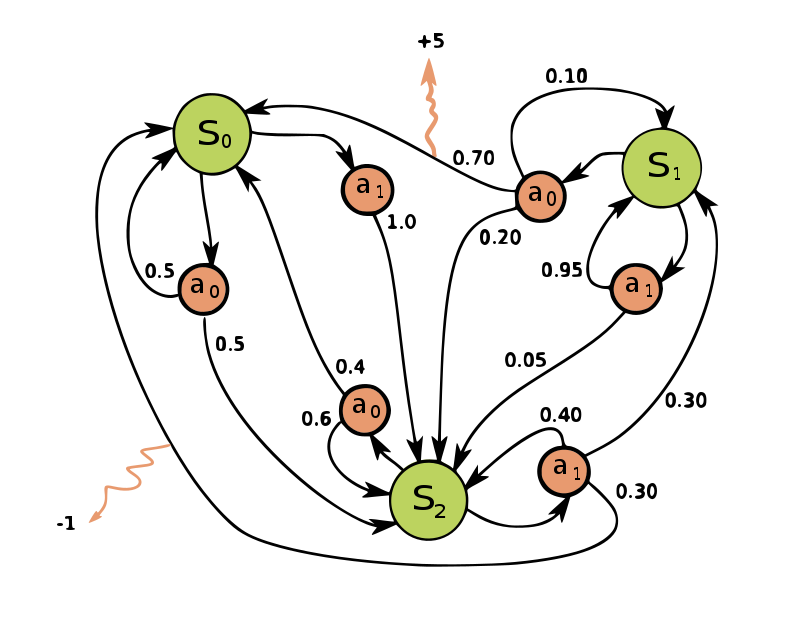

Figure 1. A simple example of an MDP with three states (green circles), two actions (orange circles) and two rewards (orange arrows).

As shown in Figure 1 [source], the simple MDP has three states ($S_0, S_1, S_2$). In which, for each state, there are two possible actions ($a_0,a_1$) and each action that is taken in state $s$ has its own unique set of transition probabilities that lead to the state at the next timestep $s’$. In Figure 1, the rewards are only available at the location indicated by the orange arrows, thus we can assume that the others have 0 rewards. Usually, this MDP can be assumed to run in a finite amount of timestep, often called finite horizon MDP (e.g. marketing campaign that runs for 3 weeks), or it can also be assumed to run indeterminately, often called infinite horizon MDP (e.g. a machine that operates 24/7 for 10 years).

The goal of the MDP is to find the optimum policy that governs the decision-maker, or agent to make the decisions that lead to the biggest cumulative reward over the given time window. For example, the optimal policy of Figure 1 could be “Always do $a_0$ in state $S_0$, always do $a_0$ in state $S_1$, and always do $a_a$ in state $S_2$” (disclaimer: I don’t know the optimal solution, it’s just a mere example).

There are several methods that are commonly used to find the optimum policy such as value iteration, policy iteration, dynamic programming, etc. However, in this tutorial, we will only cover solving the MDP using linear programming, and I also will not cover much about the theoretical background. If you are not very familiar with the concept I strongly recommend these courses to cover the theoretical background:

To make everything more concrete, let’s consider a use case of MDP to determine the optimal policy for an industrial machine maintenance.

Problem Statement

An old pasta machine operates 7 days a week from 10.00 to 18.00. Due to its central role in the pasta factory, they are subject to careful maintenance. However, due to its age, it doesn’t have any sensors. Therefore, each morning the technicians need to inspect the machine and take note of the state of the machine which are defined as: A (best), B (moderate), C (worst). Based on the machine state reading, the production manager makes a decision based on one of the following actions:

- Normal production $(N)$: The mechanics leave the machine in its current state, declaring it ready for operation in today’s shift.

- Basic maintenance $(M)$: The mechanics perform a quick basic maintenance in the morning which costs 3000 Eur. Conducting basic maintenance when the machine at state B can improve the machine’s condition to state A with $0.2$ chance (otherwise stays in state B), and conducting basic maintenance at state C can improve the machine’s condition to state B with $0.1$ chance (otherwise stays in state C). It is important to note that the machine can still operate normally after basic maintenance in the morning.

- Overhaul $(O)$: Overhauling the machine will always bring the machine’s condition back to state A. However, an overhaul takes the entire day and the machine simply becomes unproductive in that day. An overhaul costs 4000 Eur.

When a machine is used in production, there’s a possibility of its condition deteriorating or experiencing a breakdown. The probability of this occurrence is influenced by the machine’s current state. A breakdown leads to serious damage, requiring a three-day repair period (including the day of the breakdown), during which the machine cannot be used for production. On the fourth day, the machine is ready for use again in state A. On average, such a breakdown results in a net loss of 23000 Eur, factoring in all labour and material costs and the value of production before the breakdown. However, if a machine completes the entire production day without a breakdown it produces pasta that is equal to 10000 Eur of profit.

Based on the historical data, the pasta factory’s chief engineer has provided us with statistical information related to the likelihood of deteriorating and breaking down. To summarize, all information from the chief engineer is given in Table 1 below. However, some information is still missing and we need to infer from the existing information.

Table 1. Known information from the chief engineer.

| State | Action | Final State | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | Breakdown | ||

| A | Normal | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| B | Normal | - | ? | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Maintenance | 0.2 | ? | ? | ? | |

| Overhaul | 1 | - | - | - | |

| C | Normal | - | - | ? | 0.4 |

| Maintenance | - | 0.1 | ? | ? | |

| Overhaul | 1 | - | - | - | |

Additionally, the cost and profit information also provided below:

- Basic maintenance cost ($c_1$) = 3000 Eur

- Overhaul cost ($c_2$) = 4000 Eur

- Breakdown total cost ($c_3$) = 23000 Eur

- Average daily production profit ($d$) = 10000 Eur

Formulating The MDP

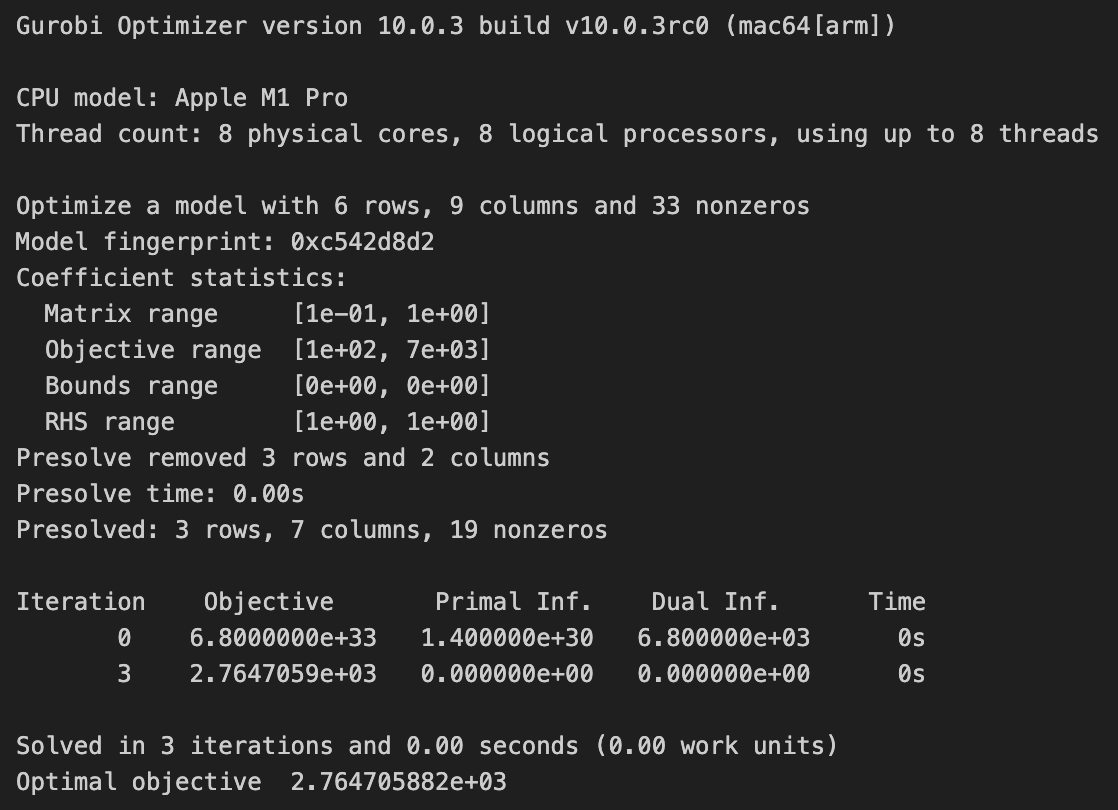

The accurate formulation of the MDP is crucial for representing the underlying dynamical system. Moreover, there are several pieces of missing information that still need to be inferred. This article will not dive deeper into the step-by-step procedure for constructing the MDP graph representation. Instead, it will present the final MDP representation and the reasoning behind it. Figure 2 below illustrates the final MDP representation of the problem.

Figure 2. MDP graph representation.

First, as our problem has an indefinite time range, and in fact, the machine is operating 7 days a week with expected usage that can exceed 2 years or so (it’s normal to expect an industrial machine to last for a long time), we can assume that our MDP is an infinite horizon MDP. Now, the let’s consider the main components of the MDP, the main states and the main actions. Here, we consider the main states to be $(A,B,C,Br_1)$ which are represented by squares and the main actions are normal operation ($N$), basic maintenance ($M$), and overhaul ($O$). Being the best state, there’s only normal operation ($N$) that we should only consider as an option in this state. Then, based on table 1, we know the probability that the machine’s state might end up and we can simply draw an arrow to the corresponding state with the probability written in green text. The same goes for states $B$ and $C$ when operating in normal conditions. However, in table 1, we are still missing $P(B|B,N)$ and $P(C|C,N)$. This can be easily solved by taking the fact that the sum of the transition probability for each action at each state should be 1:

\[\sum_{s'\in S'} P(s'|s,a) = 1,\]thus, we obtain $P(B|B,Normal) = 0.3$ and $P(C|C,Normal) = 0.6$.

Things get a bit more complicated when dealing with basic maintenance. Taking an example from the basic maintenance at state $B$, we know that the maintenance can improve the machine’s state to $A$ with probability $P(A|B,M) = 0.2$. However, we also know that the fact the machine can still operate normally after maintenance, therefore the machine is still subject to degradation or even breakdown. Thus, the transition probability of the remaining is calculated as:

- $P(B|B,M) = (1 - P(A|B,M)) \cdot (P(B|B,N)) = 0.24$

- $P(C|B,M) = (1 - P(A|B,M)) \cdot (P(C|B,N)) = 0.32$

- $P(Br_1|B,M) = (1 - P(A|B,M)) \cdot (P(Br_1|B,N)) = 0.24$.

Similarly, we can compute the transition probability for maintenance at state $C$, with the result illustrated in Figure 2. Since the overhauling always brings the machine’s condition into state $A$ and the machine cannot operate normally during that day, we represent the overhauling block as a single entity. This is because there is no difference in the transition probability and the reward value for overhauling the machine in state $B$ or $C$.

Considering the breakdown event can be a bit tricky. It is stated that:

A breakdown leads to serious damage, requiring a three-day repair period (including the day of the breakdown), during which the machine cannot be used for production. On the fourth day, the machine is ready for use again in state A.

Hence, we assume that during day 1 (the day of the breakdown) the machine is still in its current state and we need extra blocks to model the extra 2 days of inactive period. For the sake of completeness, each day we represent with a pair of state and action, day 2 is represented by a pair of $(Br_1,R)$ and day 3 is represented by $(Br_1,R)$, in which the transition probability $P(Br_2|Br_1,R) = 1$ and $P(A|Br_2,R) = 1$.

Finally, we calculate the expected reward of each action given the possible current state of the machine. To simplify, let’s start with the machine breakdown blocks first. We can assume that this part of the MDP has 0 rewards because the total breakdown cost of 23000 Euro is calculated upfront, as per the information provided in the problem statement. Therefore:

- $r(R|Br_1) = 0$

- $r(R|Br_2) = 0$

Next, the expected reward for performing an overhaul at state $B$ and $C$ is also straightforward. Due to the fact that the machine is unable to operate during that day, the expected reward for performing an overhaul at state $B$ and $C$ yields -4000 Euro reward, the minus sign indicates that the factory is losing money.

- $r(O|B) = c_2 = -4000$

- $r(O|C) = c_2 = -4000$

Then, let’s consider the normal operation at state $A$, $B$, and $C$. To calculate the expected reward, we must consider that each state has the probability of breakdown, given in Table 1, with total average loss of -23000 Euro, and not breaking down with an expected profit of 10000 Euro. The fact that the machine still generates an expected profit of 10000 regardless of which state the machine will end up in (except breakdown), makes the calculation relatively simple:

- $r(N|A) = P(Br_1 | A,N) c_3 + (1-P(Br_1 | A,N))d = 6700$

- $r(N|B) = P(Br_1 | B,N) c_3 + (1-P(Br_1 | B,N))d = 100$

- $r(N|C) = P(Br_1 | C,N) c_3 + (1-P(Br_1 | C,N))d = -3200$

Finally, we consider the maintenance scenario for states $B$ and $C$. The expected reward computing procedure for these scenarios is exactly the same with the normal operation condition, but with additional basic maintenance cost $c_1$. Hence, the calculation process becomes:

- $r(M|B) = c_2 + P(Br_1 | B,M) c_3 + (1-P(Br_1 | B,M))d = -920$

- $r(M|C) = c_2 + P(Br_1 | C,M) c_3 + (1-P(Br_1 | C,M))d = -4880$

Now, we can put everything together in the MDP where the expected reward is written in red text. From these results, it seems that the maintenance scenario does not offer any benefit since the expected reward costs the factory some money instead of generating profit. But for the details of the optimal policy, we should wait until we get the result from our linear programming method, which will be discussed in the next section.

Linear programming for solving MDP

Up to this point, you can solve the formulated MDP using other methods such as value iteration, policy iteration, dynamic programming, etc. But, in this tutorial, we will cover solving MDP using linear programming.

Note: In this tutorial, I’m using Gurobi because I have an academic license. However, you can also solve the linear programming using open-sourced free library such as CVXPY or Pyomo. Their interface might be different from Gurobi, but the general idea should stay the same.

The main objective in solving an MDP (finding the optimal policy) is to maximize the amount of cumulative reward over time. Mathematically, the expression can be written as:

\[\max \sum_{s\in S}\sum_{a\in A} r(a|s)x_{a|s},\]subject to:

\[\sum_{s\in S}\sum_{a\in A} x_{a|s} = 1,\] \[\sum_{a\in A} x_{a|s} = \sum_{s'\in S}\sum_{a\in A} p(s|s',a)x_{a|s'} \quad \forall s \in S,\] \[x \geq 0\]where $x_{a|s}$ is the probability that we are choosing action $a$ when we are in state $s$ when considering random period. The term $r(a|s)$ simply states our reward of doing action $a$ in state $s$, and $p(s|s’,a)$ is the transition probability of reaching state $s$ when we are in state $s’$ and taking action $a$. At first, it might seem a little bit confusing. But we will take a closer look when formulating the problem in our LP solver.

First, let’s import the Python library and initiate our LP model:

import numpy as np

import gurobipy as gp

lp = gp.Model()

Now let’s define the decision variables $x_{a|s}$ to the model. Take note that because we have our third constraint $x \geq 0$, we put it directly in our variable bounds.

# Adding variables to the model

# args `lb=0.0` means the lower bound of the variable is 0.0

x_AN = lp.addVar(name="x_AN", lb=0.0)

x_BN = lp.addVar(name="x_BN", lb=0.0)

x_BM = lp.addVar(name="x_BM", lb=0.0)

x_BO = lp.addVar(name="x_BO", lb=0.0)

x_CN = lp.addVar(name="x_CN", lb=0.0)

x_CM = lp.addVar(name="x_CM", lb=0.0)

x_CO = lp.addVar(name="x_CO", lb=0.0)

x_Br1R = lp.addVar(name="x_Br1R", lb=0.0)

x_Br2R = lp.addVar(name="x_Br2R", lb=0.0)

Considering the objective function of the MDP:

\[\max \sum_{s\in S}\sum_{a\in A} r(a|s)x_{a|s},\]since the $r(a|s)$ component is already predetermined by the existing information, we can only control the decision variable $x_{a|s}$. In the objective function context, this roughly translates to “Maximize the total reward by choosing the right decision variable $x_{a|s}$”. Thus for our specific case, the objective function expression can be alternatively written as:

\[\max r(N|A)x_{N|A} + r(N|B)x_{N|B} + r(M|B)x_{M|B} + r(O|B)x_{O|B} + r(N|C)x_{N|C} + r(M|C)x_{M|C} + r(O|C)x_{O|C}\]For the sake of conciseness, we can directly plug each value of the rewards. In Python, this is written as:

# Define the objective function

lp.setObjective(6700*x_AN + 100*x_BN - 920*x_BM - 4000*x_BO - 3200*x_CN - 4880*x_CM - 4000*x_CO, gp.GRB.MAXIMIZE)

Next, we have our first constraint. This constraint simply tells us that the sum of the probability of the action that we take considering a random period should be one. At this point, the decision variable $x_{a|s}$ might seem a bit abstract. Why do we consider probability to represent a decision that we should take? For now, let’s leave it as is and we will come back later in the result discussion.

\[\sum_{s\in S}\sum_{a\in A} x_{a|s} = 1,\]In our case, this expression translates as:

\[\sum x_{N|A} + x_{N|B} + x_{M|B} + x_{O|B} + x_{N|C} + x_{M|C} + x_{O|C} + x_{R|Br_1} + x_{R|Br_2} = 1\]In python:

# Add first constraint

c1 = lp.addConstr(x_AN + x_BN + x_BM + x_BO + x_CN + x_CM + x_CO + x_Br1R + x_Br2R == 1, "action prob")

Then, let’s take a look at the second constraint. While looks a bit confusing the constraint simply states that for each state node, the “amount” or “magnitude” of the incoming arrow should equal to the outgoing arrow. Thus, this expression:

\[\sum_{a\in A} x_{a|s} = \sum_{s'\in S}\sum_{a\in A} p(s|s',a)x_{a|s'} \quad \forall s \in S,\]For each state node, rewrites as:

- $x_{N|A} = p(A|A,N)x_{N|A} + p(A|B,M)x_{M|B} + p(A|B,O)x_{O|B} + p(A|C,O)x_{O|C} + p(A|Br_2,R)x_{R|Br_2}$

- $x_{N|B} + x_{M|B} + x_{O|B} = p(B|A,N)x_{N|A} + p(B|B,N)x_{N|B} + p(B|B,M)x_{M|B} + p(B|C,M)x_{M|C}$

- $x_{N|C} + x_{M|C} + x_{O|C} = p(C|A,N)x_{N|A} + p(C|B,N)x_{N|B} + p(C|B,M)x_{M|B} + p(C|C,M)x_{M|C} + p(C|C,N)x_{N|C}$

- $x_{R|Br_1} = p(Br_1|A,N)x_{N|A} + p(Br_1|B,N)x_{N|B} + p(Br_1|B,M)x_{M|B} + p(Br_1|C,M)x_{M|C} + p(Br_1|C,N)x_{N|C}$

- $x_{R|Br_2} = p(Br_2|Br_1,R)x_{R|Br_1}$

In python, this is written as:

# Add second constraint

c2 = lp.addConstr(x_AN == 0.4*x_AN + 0.2*x_BM + x_BO + x_CO + x_Br2R, "state A constr")

c3 = lp.addConstr(x_BN + x_BM + x_BO == 0.3*x_AN + 0.3*x_BN + 0.24*x_BM + 0.1*x_CM, "state B constr")

c4 = lp.addConstr(x_CN + x_CM + x_CO == 0.2*x_AN + 0.4*x_BN + 0.32*x_BM + 0.6*x_CN + 0.54*x_CM, "state C constr")

c5 = lp.addConstr(x_Br1R == 0.1*x_AN + 0.3*x_BN + 0.24*x_BM + 0.4*x_CN + 0.36*x_CM, "state Br1 constr")

c6 = lp.addConstr(x_Br2R == x_Br1R, "state Br2 constr")

Finally, we can run our program:

lp.optimize()

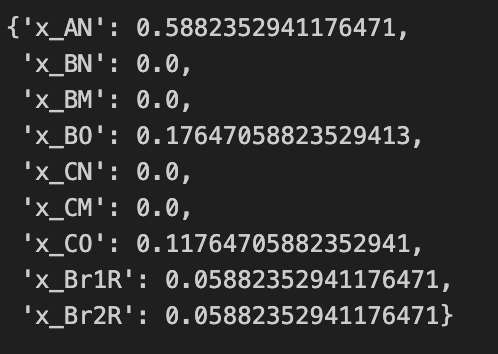

While running the program, we should have display as shown in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3. Solver display.

Now, we extract the result:

{var.VarName : var.x for var in lp.getVars()}

Figure 4. Optimal policy.

Our result shows that the optimal policy is:

| State | A | B | C | Br_1 | Br_2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Normal | Overhaul | Overhaul | Repair | Repair |

With reward of $\approx 2765$ Euro.

Now, we get back to interpreting the decision variable. Let’s take a look for example $x_{O|B} \approx 0.1765$, this expression of probability simply translates to the expected frequency of occurrence. Thus, it can be interpreted as “If we follow the optimal policy and run the MDP for 10000 timesteps (days), then we expect to find the machine in state $B$ and make the decision to overhaul the machine approximately 1765 times.”

How to cite this article:

@misc{faza2024mdplptutorial,

author = {Faza, Ghifari Adam},

title = {Tutorial on solving Markov Decision Process with linear programming},

month = {May},

year = {2024},

url = {https://fazaghifari.github.io/posts/2024/05/mdp-lp-en/},

}